Table of contents

A practical guide to Schach, shade, and Sukkah builders

Every year, as soon as the first wooden panels go up and the smell of fresh bamboo mats fills the air, the same quiet questions start circulating.

Who built this Sukkah?

Does it matter who built it?

And while we’re at it – could someone theoretically just throw a stack of paper on top and call it Schach?

Sukkot has a funny way of turning otherwise practical people into amateur halachic detectives. And honestly, that’s part of the charm. Beneath the fairy lights and paper chains lies a festival packed with legal nuance, ancient sources, and just enough debate to keep things interesting.

Let’s tackle two surprisingly common Sukkah questions – one about who builds the Sukkah, and one about what goes on top of it.

Can a Non-Jew Build a Sukkah? (Yes. Really.)

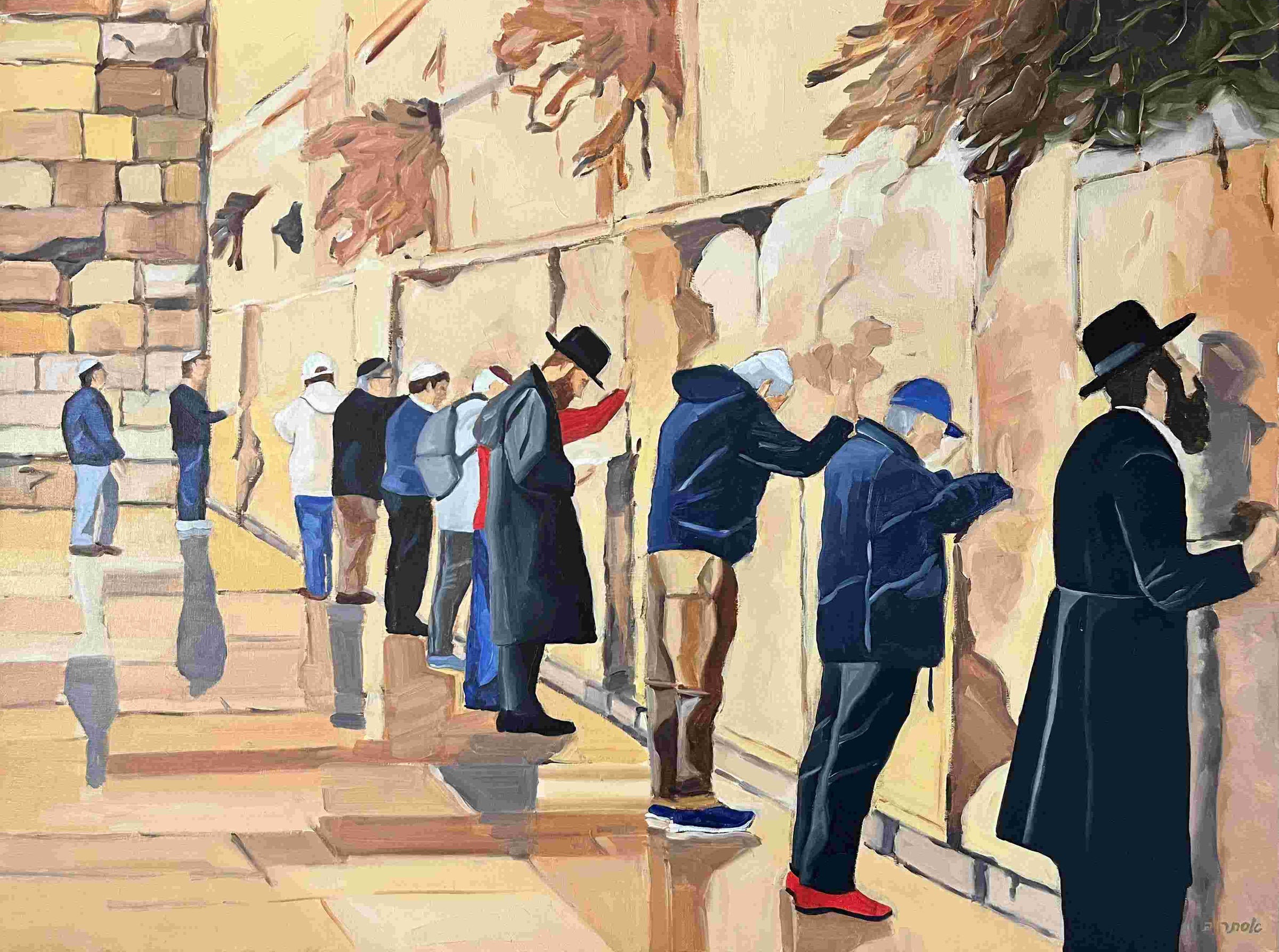

Walk into many synagogues or communal courtyards, and you’ll see a familiar scene: a hired caretaker or contractor assembling the Sukkah from start to finish, Schach included. This sometimes raises eyebrows.

Isn’t there some requirement that a Jew must build the Sukkah?

At least the roof?

At least something?

The short answer: a Sukkah built entirely by a non-Jew is valid.

The longer answer takes us straight to the Talmud.

A Sukkah Is a Sukkah Is a Sukkah

The Talmud (Sukkah 8b) explicitly discusses a Sukkah built by non-Jews and rules that it is valid – as long as it was made for shade (לצל, l’tzel) and has proper Schach. This ruling is codified in the Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim 635, which is the standard halachic code for daily Jewish practice.

Why does “shade” matter so much?

Because the word Sukkah itself means a shade-providing shelter. Even according to the opinion that a Sukkah does not need to be built specifically for the holiday (a view associated with Beit Hillel in Sukkah 9a), it still needs to function as a real shelter from the sun. A decorative structure with sunlight streaming straight through simply doesn’t count.

So if a non-Jew builds a hut for shade – and it meets all the technical requirements of Schach – it’s halachically a Sukkah. Full stop.

But Isn’t Building the Sukkah a Mitzvah?

Here’s where things get interesting.

The actual biblical mitzvah of Sukkot is to dwell in the Sukkah, not to build it. Eating, sleeping, and living in the Sukkah for seven days – that’s the obligation. Building it is more like mitzvah-adjacent. Important, meaningful, and spiritually loaded, but not technically required.

That’s why halachically, someone can fulfill the mitzvah perfectly in a Sukkah they didn’t build themselves at all – including one built by a non-Jew (Shulchan Aruch OC 635).

L’chatchila vs. B’dieved: The Halachic Fine Print

Even though the Sukkah is valid, some later authorities introduce a distinction between:

B’dieved (בדיעבד): after the fact, valid

L’chatchila (לכתחילה): ideally, preferred

Some opinions suggest that ideally, a Jew should participate in the construction – especially the placement of the Schach. Why? Because there’s value in personally engaging in preparations for a mitzvah, even if it’s not strictly required.

One commonly suggested solution is beautifully simple: lift a piece of Schach and put it back down with the intention that it’s for the mitzvah of Sukkah. This small action symbolically connects the Jew to the construction, even if everything else was already done (Mishnah Berurah 635:1).

That said, many authorities note that even this step is not required, especially if the non-Jew was hired specifically to build the Sukkah on behalf of a Jew. In halachic terms, hired labor is often considered an extension of the employer’s actions (see Machaneh Ephraim, Hilchot Shluchin §11).

Translation: if you paid someone to build your Sukkah, you’re still very much in the clear.

What About the Shehecheyanu?

Some people assume that since the Shehecheyanu blessing (the “thank You for keeping us alive” blessing) is recited on the first night of Sukkot, it must be tied to building the Sukkah.

It isn’t.

That blessing is recited for the arrival of the festival and the opportunity to perform its mitzvot – not for the construction itself. So no, you don’t lose points (or blessings) if you didn’t personally wield the hammer.

Now for the Roof: Can Paper Be Used as Schach?

At first glance, paper seems promising.

It comes from trees.

Trees grow from the ground.

Schach must come from things that grow from the ground (gidulei karka).

So… paper?

Nice try. But no.

Why Schach Has to Look…Natural

One of the core rules of Schach is that it must be made from natural materials that grow from the ground and are not significantly processed.

This requirement appears in the Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 629:4–5) and is elaborated on by the Magen Avraham there. The more a material is altered from its original form, the more problematic it becomes.

Wood planks? Fine.

Palm branches? Perfect.

Bamboo poles? Classic.

Paper, however, has been pulped, pressed, dried, flattened, and fundamentally transformed. By the time it reaches your printer tray, it no longer resembles its natural source in any meaningful way.

That level of processing disqualifies it as Schach.

But Paper Doesn’t Receive Tum’ah!

Another common argument goes like this: paper is not a vessel (kli), doesn’t have a receptacle, and therefore does not receive ritual impurity (tum’ah). And one of the rules of Schach is that it must not be susceptible to tum’ah.

True – but incomplete.

Schach must meet all the requirements, not just one. Being immune to tum’ah isn’t enough if the material fails the “natural, unprocessed” test.

That’s why paper, cotton wool, flax rope, and other heavily processed plant materials are all invalid for Schach (Shulchan Aruch OC 629; Magen Avraham ad loc.).

So Why Has No One Ever Tried It?

Because halacha aside, paper also fails the practical Sukkah test.

Wind.

Rain.

Gravity.

Even if it were theoretically allowed, a paper-roofed Sukkah would last approximately three minutes – and that’s on a calm day.

The Takeaway: Sukkot Is Serious…and Flexible

Sukkot is full of structure, rules, and measurements – but it’s also refreshingly forgiving.

A Sukkah built entirely by a non-Jew? Valid.

One built months earlier, for shade, not the holiday? Still valid.

Schach that’s natural, simple, and a little rustic? Perfect.

What matters most is not perfection in construction, but presence in the mitzvah – actually living, eating, and celebrating inside the Sukkah.

And if someone else built it for you? Even better. You can focus on what the Sukkah was always meant for: stepping outside, looking up through the Schach, and remembering that sometimes the best spiritual experiences don’t require doing everything yourself.