Table of contents

The Passover Seder is a masterpiece of tradition and storytelling, designed to transport us back in time to relive the Exodus from Egypt. Among its many highlights is the moment the youngest at the table sings or recites the Mah Nishtanah, often dubbed the "Four Questions." But here’s the plot twist: they aren’t really questions! And that’s not a glitch in the system – it’s a feature. Let’s explore why these so-called "questions" matter, and how they frame the Seder experience.

Are They Really Questions? Spoiler: Nope!

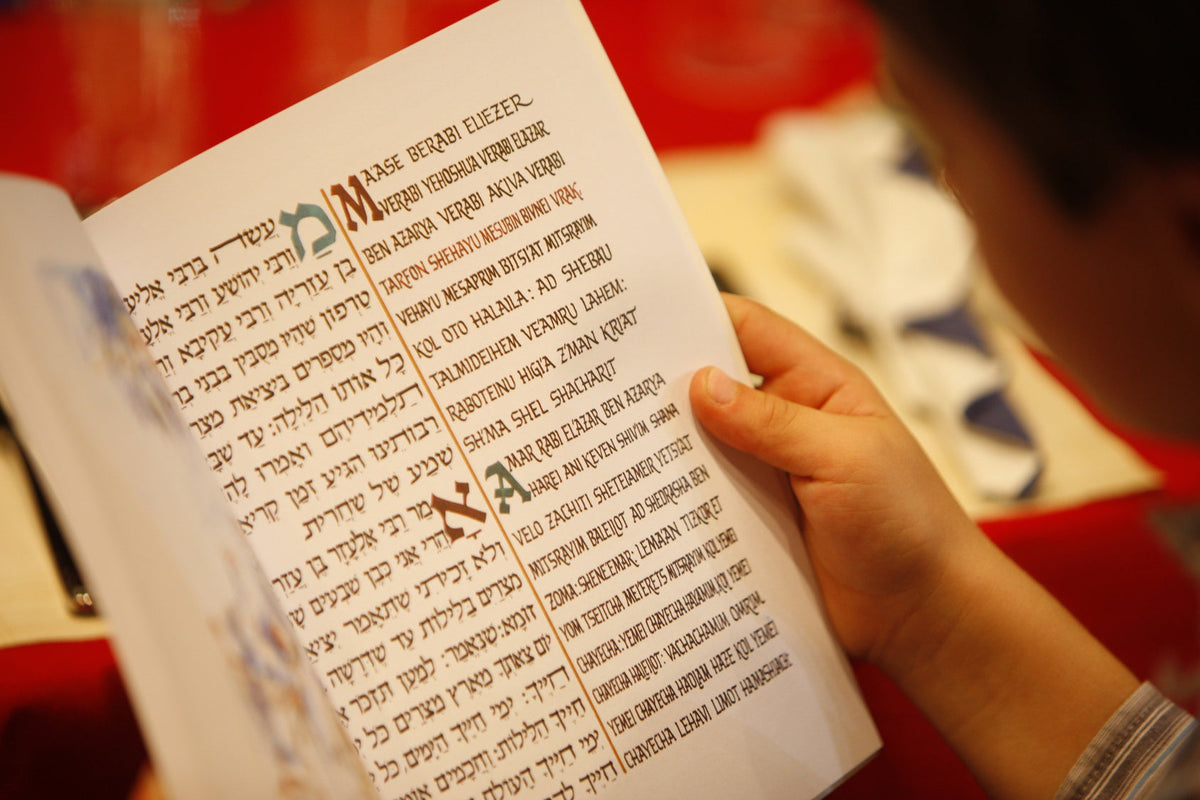

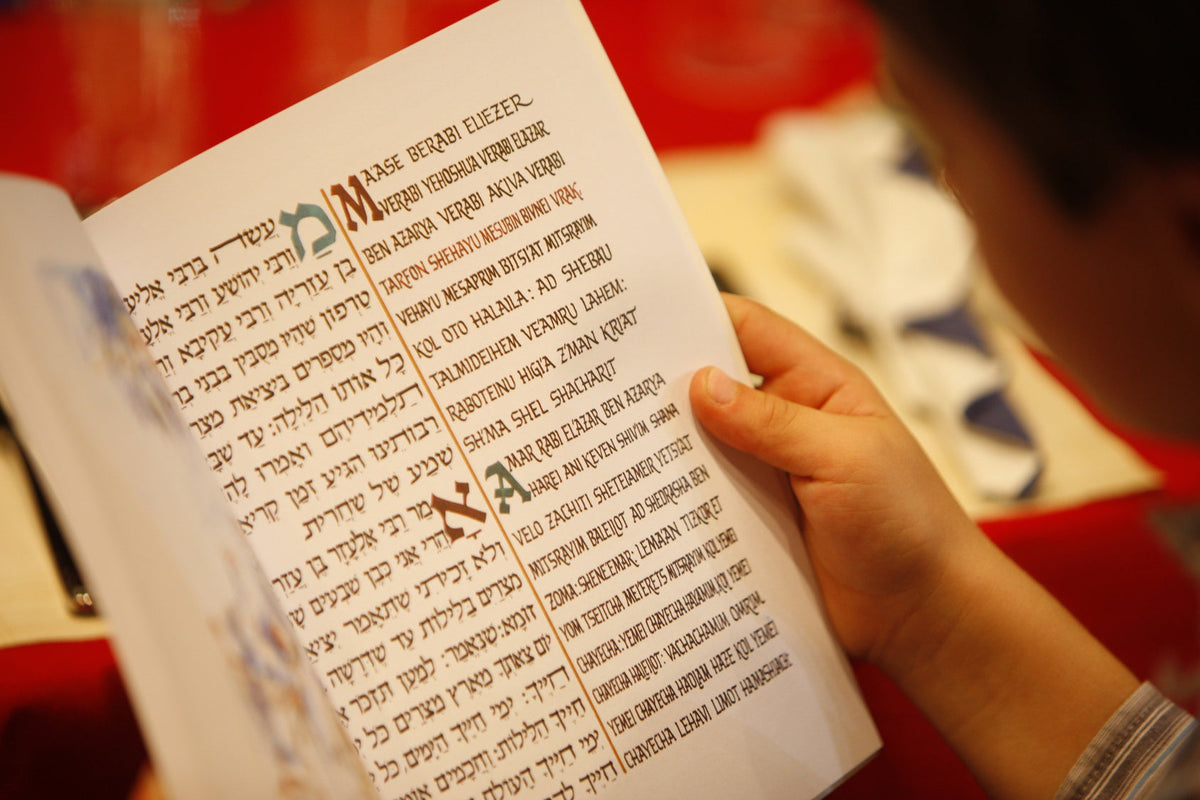

Let’s review the text of the Mah Nishtanah aka. 'The Four Questions.'

On all other nights, we eat chametz or matzah, but tonight, only matzah .

On all other nights, we eat all kinds of vegetables, but tonight, only maror .

On all other nights, we don’t dip even once, but tonight, we dip twice.

On all other nights, we eat sitting upright or reclining, but tonight, we all recline.

These statements don’t exactly end with a question mark. In Hebrew grammar, they’re structured as observations that highlight differences, not direct inquiries. So why call them "questions"?

The Question That Matters

The introductory line of the Mah Nishtanah asks the real question: "Why is this night different from all other nights?" This overarching question frames the entire evening. The purpose isn’t to demand answers but to spark curiosity. And what better way to do that than with the declarative "questions" that follow?

Why the Seder Night Is All About Curiosity

The Seder’s design isn’t just for the sake of tradition – it’s to engage everyone , especially children. The Talmud (Pesachim 116a) emphasizes that the Seder should inspire questions and discussion. That’s why we do things differently: eating unusual foods, dipping vegetables, and leaning like royalty. These practices aren’t arbitrary; they’re meant to provoke the ultimate "Why?"

Curiosity is the engine of the Seder . By structuring the Mah Nishtanah as observations, the rabbis ensured that even young children could recognize the unusual elements and ask about them. This format creates a moment where children take center stage, and everyone around the table becomes a participant in the story.

Breaking Down the Four "Questions"

1. Matzah: The Bread of Affliction

Why only matzah tonight? The Torah (Deuteronomy 16:3) refers to matzah as "lechem oni" – the bread of affliction. It reminds us of the haste with which our ancestors fled Egypt, leaving no time for their dough to rise.

But matzah is more than a history lesson. It’s a symbol of humility. Unlike chametz, which puffs up with yeast (and metaphorical ego), matzah stays flat and unpretentious. Eating it reminds us to let go of arrogance and embrace simplicity.

Pro Tip for Parents: When explaining this to kids, call matzah the "anti-pizza" to really drive home the lack of fluff.

2. Maror: The Bitter Reality

On all other nights, we eat all kinds of vegetables, but tonight, it’s all about maror , the bitter herb. Maror represents the bitterness of slavery in Egypt (Exodus 1:14). Its sharp taste is meant to jolt us, making the experience of hardship tangible.

Fun fact: Sephardic Jews often use romaine lettuce stems, while Ashkenazim go for the more tear-inducing horseradish. Both options really bring home to us that bitterness isn’t just an idea – it’s an experience.

3. Dipping Twice: A Double Dose of Meaning

We don’t dip even once on regular nights, but tonight, we double-dip. First, we dip karpas (a vegetable, usually parsley or celery) in salt water, symbolizing the tears shed by the Israelites in slavery. Later, we dip maror into charoset, a sweet mixture of nuts, apples, and wine, symbolizing the mortar used by enslaved Jews to build for Pharaoh.

The dual dipping represents contrast: from tears to sweetness, from hardship to hope. It’s a tactile way to explore the Exodus story, reminding us that redemption often comes after struggle.

4. Reclining Like Royalty

In ancient times, free people ate while reclining on couches or cushions, while slaves ate standing or hunched over. By reclining at the Seder , we celebrate our freedom, honoring the transformation from slaves to dignified members of society.

Pro tip: If reclining feels awkward in your dining chairs, give it your best try – it’s about the symbolism, not perfect form.

The Role of Children at the Seder

The Mah Nishtanah’s primary goal is to involve children in the Seder . Rabbi Yosef Karo, in the Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chayim 472), explains that engaging children with these questions ensures the continuation of Jewish tradition. When kids ask why the night is different, they’re actively participating in the storytelling process, fulfilling the commandment to teach our children (Exodus 13:8).

Even if there are no children at the Seder , adults must ask the questions instead, as we should all be exemplifying a sense of childlike curiosity at the Seder .

A Historical Note: The Changing Questions

Did you know the Mah Nishtanah has evolved over time? The Mishnah (Pesachim 10:4) includes a version that asks about roasting the Paschal lamb – a practice that’s no longer common. Other versions asked why we eat only roasted meat on Pesach . As Jewish practices changed, so did the "questions," showing the adaptability of tradition.

So, the next time the youngest at your table belts out the Mah Nishtanah – whether it’s with perfect pitch or delightful chaos – soak it all in. Those "questions" are doing exactly what they’re supposed to: sparking curiosity, igniting conversation, and reminding us why this night really is different from all others. It’s a celebration of freedom, family, and yes, even the occasional matzah crumb avalanche.